Concatenating Strings

A string has one basic operator: +

. The plus sign concatenates (in other words, joins together) two strings. Permit me to demonstrate:

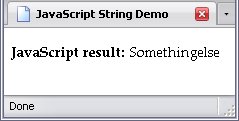

var word_1 = "Something";var word_2 = "else";document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.data = word_1 + word_2;You may be wondering, Where'd the space go?

Well, if you look closely at the code, the space simply isn't there. word_1 doesn't have it, neither does word_2, and it was not added in at any time. This is important, JavaScript doesn't care about what results it spits out, it's just following orders. So let's add in a space:

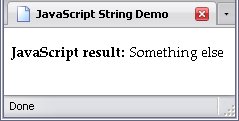

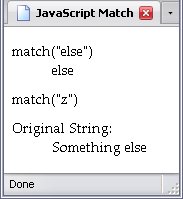

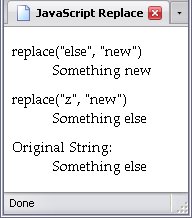

var word_1 = "Something";var word_2 = "else";document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.data = word_1 + " " + word_2;Yes you can use more than one operator in an equation. And now the value of foo is Something else

.

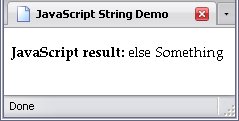

But do remember that the order that the strings are placed in are important. In the example below, I will switch word_1 and word_2 when concatenating them:

var word_1 = "Something";var word_2 = "else";document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.data = word_2 + " " + word_1;Adding Text To A String

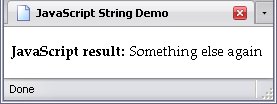

Concatenation allows you to adjust the text value of a variable. For example, if foo holds the value Something else

, and you want to add the text again

, it's really easy to do:

var foo = "Something else";" again";document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.data = foo;Concatenation Shorthand

The short-hand expression for adding text uses a combination of the +

and =

operators: +=

. This operator tells the script that the following text is to be added to the text already contained in the variable. This text will always come after, not before.

var foo = "Something else";" again";