Back in CSS Selectors, I mentioned that there were four psuedo-elements—elements which don't really exist outside of the stylesheet (this is why they have to come last in a selector):

- :first-letter

- :first-line

- :before

- :after

The first two have content

(after a fashion), that being the first letter in an element and the first line of text in an element, respectively.

The second two don't; their content must be specified through the content property.

CSS-generated content can be text (including special charactersand the contents of any of the element's attributes, counters, quote marks, images, or any combination of the above. CSS-generated content is supported by most modern browsers (including Internet Explorer 7 and up), but older browsers are still common (there are people who still use Internet Explorer 4!), so you'll want to consider that.

So long as a pseudo-element has content, it can be styled like any other element.

Text

In computing, a text character is a character you can type with your keyboard (digits, letters of the alphabet, punctuation marks, etc.) and a string is a sequence of them. For the :before and :after psuedo-elements, text characters and strings are the simplest content to specify and examples of this are sprinkled all over this manual. If your browser supports it (and most modern ones do, though Internet Explorer 6 and older does not), you've likely noticed that element names (such as html) have <

before and >

after them—but if you view the code, those symbols are nowhere in sight. That's because those symbols are in the stylesheet, not the (X)HTML document. Below is the CSS rule, taken straight from book_main.css:

*.el_name:before,

*.el_names > li:before,

dl.el_names > dt:before,

*.tag:before

{content:"<";}

*.el_name:after,

*.el_names > li:after,

dl.el_names > dt:after,

*.tag:after

{content:">";}

As with (X)HTML attributes, you can use either double or single quotes; just make sure they're properly paired.

The results can be seen with:

- Any element (usually

code) that has the el_name

or tag

class (there are several for the former in this list).

- Any

li element that's a child of an element (ideally ul and ol for the code to be valid) that has the el_names

class;

- Any

dt element that's a child of a dl element that has the el_names

class.

Special Characters in CSS

In Special Characters, I talked about Unicode and hexadecimal Numeric Character References. CSS also uses them but there are several differences from those in (X)HTML.

Comparing (X)HTML And CSS NCRs

|

(X)HTML |

CSS |

| Beginning Character(s) |

&#x |

\ |

| Max number of digits |

Four |

Six |

| Preceding zeroes can be eliminated |

Yes |

| Ending Character |

; |

None |

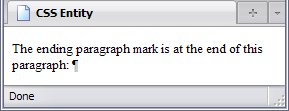

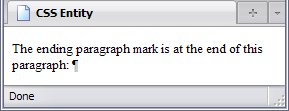

<style type="text/css">

p:after{content:"\0000B6";}

</style>

. . .

<p>The paragraph mark is at the end of this paragraph: </p>

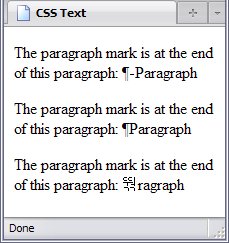

Issues With CSS NCRs

A danger exists when it comes to CSS NCRs: as stated in the table above, they have have no specific end character. Instead, they end only when they encounter a character that is not a hexidecimal digit or when it reaches the six digit limit. In the following stylesheet, #p_1 and #p_2 will show the paragraph mark and its following text. However, in the rule for #p_3, Paragraph

is misspelled Baragraph

—and since both B

and a

are hexidecimal digits (case does not matter), one would expect the character corresponding to \00B6BA

(뚺

in (X)HTML notation) to appear.

#p_1:after{content:"\B6-Paragraph";}

#p_2:after{content:"\B6Paragraph";}

#p_3:after{content:\B6Baragraph";}

Which it does; the unexpected character (뚺

) is a Hangul (the Korean system of writing) syllabic block. This is not because Paragraph

is misspelled; browsers couldn't care less about spelling (unless it's the spelling of an element or attribute name, or CSS property or value). Instead, this occurs because this particular misspelling begins with the letters Ba

—letters the browser confuses for hexadecimal digits.

I warned you about confusing the browser.

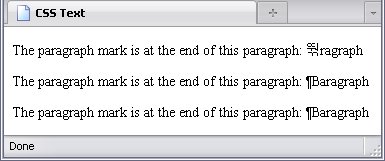

There are a few ways to fix this. Below I show two of them. First is the erroneous rule, the next two are two ways around it:

#p_1:after{content:"\B6Baragraph";}

#p_2:after{content:"\B6 Baragraph";}

#p_3:after{content:"\0000B6Baragraph";} */

In the second two paragraphs, the typo is revealed for all to see.

Notice that a single space right after an NCR is ignored, and would be even if Paragraph

were spelled correctly. If you want a space after an NCR, you have to use two spaces.

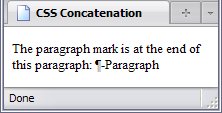

Concatenation

In any computer language, concatenation means joining two strings of characters. In CSS, concatenation is very simple: Simply follow one string or character with another:

p:after{content:'\B6' "-Paragraph";}

The result can be seen below:

That's pretty much it. No special symbols needed. In this case, concatenation might seem like needlessly complicating things, but strings aren't the only thing you can use for content—nor does a string of characters necessarily have to come from the stylesheet itself.

Text From Attributes

Another source of text is the element's attributes. Unfortunately, you can't use the attribute of a parent or a sibling element (at least as of CSS 3); instead you are limited to the element that's being given the pseudoelement.

Allow me to demonstrate:

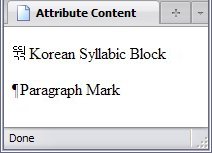

p:after{content:attr(title);}

. . .

<p title="Korean Syllabic Block">뚺</p>

<p title="Paragraph Mark">¶</p>

The attribute name (in this case, title) is not in quotes; it's a reference to an attribute, not text. Below, you can see the results:

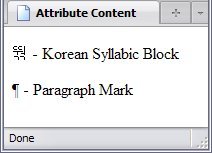

Here is where concatenation comes in rather handy: you can combine a string with the content from an attribute:

p:after{content:' - ' attr(title);}

. . .

<p title="Korean Syllabic Block">뚺</p>

<p title="Paragraph Mark">¶</p>

A note on special characters within attributes: since they're defined in the (X)HTML document itself instead of in the stylesheet, you would use the (X)HTML instead of the CSS method, and yes, character entity references would work as well.

Counters

Like ordered lists, counters use numbers or the like to keep track of various items in the page, but counters allow numbering for things that aren't in an ordered list. For example, all the numbering on my examples and images in this book was done using counters. But they don't do it automatically; you actually have to tell the browser which counter to increment, when, and by how much—along with the beginning value of each counter.

There are three names you must not use for counters, since they have special meaning in CSS: none

, since that means no counter

; inherit

, since that has its usual meaning here; and initial

, which is reserved for future use.

(Re)Setting a Counter

| Property: | counter-reset |

|---|

| Default value: | none |

|---|

| Inherited: | No |

|---|

Setting and resetting a counter are the same thing; if you haven't created a counter earlier, this property creates that counter.

{counter-reset:counter1;}

The above creates a counter called counter1 and sets it to the default value (0). If you want to set a counter to a different, you follow the counter name with the integer:

{counter-reset:counter1 1};

If you want to set multiple counters, the following will not work:

{

counter-reset:counter1 1;

counter-reset:counter2;

}

Since cascading style sheets cascade, only counter2 will be reset; counter1 won't. Instead, you have to reset them together.

{counter-reset:counter1 1 counter2;}

In the above example, counter1 will be set to 1

, and counter2 will be set to 0

. You can reset as many counters as you like using this; the following integer for each is optional (but required if you're resetting the counter to anything other than 0)

If you want to reset a counter to, say, 0.1

, you're going to have to do some trickery to get around the fact that counters use integers only. If you want to set a counter to a negative integer, well, that is simple:

{counter-reset:counter1 1 counter2 counter3 -1;}

In the above scenario, counter1 will be set to 1, counter2 (which isn't followed by a number) will be set to 0, and counter3 will be set to -1.

Not Resetting A Counter

Say, for every div element you wanted counter1 to be reset, unless that div element was nested inside another div element?

What you would do is make a rule that says increment counter at every div element

:

div{counter-reset:counter1;}

Then you add a rule that says for every div element nested inside another div element, don't reset anything

:

div{counter-reset:counter1;}

div div{counter-reset:none;}

Making a Counter Count

| Property: | counter-increment |

|---|

| Default value: | none |

|---|

| Inherited: | No |

|---|

The counter-increment property shares a lot with counter-reset. Both use positive and negative integers along with 0, multiple counters have to be reset or incremented together, you can choose not to increment any counters using the none keyword, and the syntax is virtually identical as well. However, the major difference in the way they work is the default value for counter-reset is 0, while the default value for counter-increment is 1. This is why, in the example below, I specify that counter1's initial value is 1

, but that counter2 is incremented by 0

.

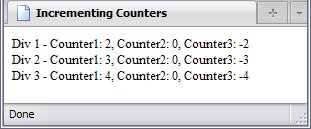

Incrementing Those Counters With The div Element

body{counter-reset:counter1 1 counter2 counter3 -1;}

div{counter-increment:counter1 counter2 0 counter3 -1;}

After being set and incremented, the three counters' values are:

Counter Values

| Name |

Initial Value |

Incremented By |

Value after 1st div |

Value after 2nd div |

Value after 3rd div |

| counter1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| counter2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| counter3 |

-1 |

-1 |

-2 |

-3 |

-4 |

Putting a Counter To Work

When you want to put the value of a counter in your content, you do it through the content property, but you do it through a special way:

{content:counter([counter name]);}

You would replace [counter name]

with the name of the counter you are using.

You can concatenate the counters like the rest of the text:

div:after{content:' - Counter1: ' counter(counter1) ', ' 'Counter2: ' counter(counter2) ', ' 'Counter3: ' counter(counter3);}

The only actual text in the HTML is Div 1

, Div 2

, and Div 3

.

Now, notice that the counter name is not in quotes. That's because it's not actual text; it's a reference to a counter.

Counter Number Style

If you want letters or roman numerals instead of your usual numbers, that's something easy enough to do: you can use a value for list-style-type to choose your numbering style. The syntax is really simple:

div:after{content:'counter(counter1, upper-roman) ', ' 'Counter2: ' counter(counter2) ', ' 'Counter3: ' counter(counter3);}

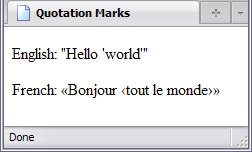

Quotation Marks

Quotation marks are language-specific. English uses the familiar apostrophe and double-apostrophe, but French uses something else.

Below is the stylesheet for this page:

q:lang(en){quotes:'"' '"' "'" "'";}

q:lang(fr){quotes:'\00AB' '\00BB' "\2039" "\203A";}

q:before{content:open-quote;}

q:after{content:close-quote;}

As you can see, French has another set of quotation marks altogether: «

, »

, ‹

, and ›

. The quotes are defined in the order of outermost-to-innermost

using the quote: property, and the page will repeat the pattern. You can specify as many pairs as you like, so long as you specify at least one pair.

As for q:before{content:open-quote;} and q:after{content:close-quote;}, you might be able to leave them out. However, it will give some strange results if you have the rules q:after{content:open-quote;} and q:before{content:close-quote;}.

Images

This is fairly straightforward: use the image's URI as described in CSS Value Types. An example is the images at the bottom of this webpage (they appear on the screen, not in print). In book_screen.css, there is a rule that specifies the :after pseudo-element for the body element, and gives it an image as content (and a second as a background):

body:after{

display:block;

background:#fff url('../Pictures/vcss.png') scroll no-repeat right 10px;

content:url('../Pictures/vxhtml.png');

border-top:1px solid black;

margin-top:10px;

padding-top:10px;

}

The declarations mean (in order)

- The

:after pseudo-element is to be displayed as a block element

- Its background

- is coloured white,

- uses the image at

../Pictures/vcss.png,

- scrolls with the rest of the page,

- not repeated,

- way over on the right,

- and 10 pixels from the top.

- The pseudoelement's content is the image

../Pictures/vxhtml.png.

- The top border is a solid black line 1 pixel thick.

- It has a top margin of 10 pixels.

- It has a top padding of 10 pixels.

You can see the results below: the content image is on the left, while the background image is on the right.

Pseudoelements In This Manual

I actually use CSS-generated content extensively in this manual. When I was writing this manual, I had no idea what order the chapters would ultimately be in, and changing the numbers when the order changed became tedious indeed. So, I set up a stylesheet (chapter_numbers.css) that set the counter numbers chap_num, chap_ref, app_num, and app_ref according to the order the chapters and appendices were in.

Chapter And Appendix Reference Links

One example of these counters being used in this manual is the chapter and appendix reference links. Each reference link is given the appropriate class to set the counter (be it chap_ref or app_ref) to the right number, and then the link is given a second class (chap_title_ref

or app_title_ref

) to tell the browser how to process it.

*.chap_title_ref, *.app_title_ref{font-style:oblique;}

*.chap_title_ref:before,

*.chap_title_ref:after,

*.app_title_ref:before,

*.app_title_ref:after

{font-style:normal;}

*.chap_title_ref:before{content:'Chapter ' counter(chap_ref) ' (';}

*.app_title_ref:before{content:'Appendix ' counter(app_ref, upper-alpha) ' (';}

*.chap_title_ref:after, *.app_title_ref:after{content:')';}

Then, if the order was changed, I merely needed to change a couple numbers in the chapter_numbers.css stylesheet. You can view the reference link rules in The Main Stylesheet For This Book. By the way, the previous a element has the app_title_ref

and appendices-stylesheet

classes.