Object Creation

There are two ways to create an object: Either directly (which has its own shorthand method) or through a template.

Directly Creating An Object

Directly creating an object is actually quite easy. First, you create a variable (object), and say that it is a new object (You've done this for arrays).

var object = new Object();Then we decide what properties it's supposed to have. Properties, of course, follow the object name with a period between the object name and property name (object.propertyNum1, Num2, Num3, and String:

var object = new Object();Num1 = 4;Num2 = 5;Num3 = 6;String = "Something Else";Now where have we seen THAT syntax before? Oh, yes, we used the data property of a text node.

So when we want to use these values, say to write to various elements, we can use their values like any other variable:

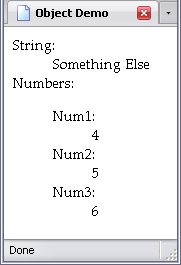

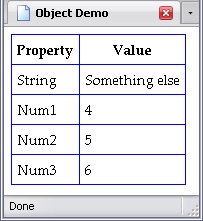

var dds = document.getElementsByTagName("dd");firstChild.data = object.String;firstChild.data = object.Num1;firstChild.data = object.Num2;firstChild.data = object.Num3;And the results are below:

Now, you might be thinking But object doesn't HAVE those properties.

Actually, when you say, Property A of Object B has Value C

, you're also saying Object B has Property A

.

I'll show you, working with nodes.

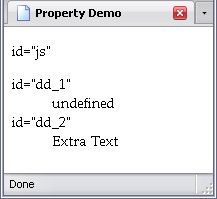

var dd1 = document.getElementByID("dd_1");var dd2 = document.getElementByID("dd_2");var js = document.getElementByID("JS");data = js.extra;extra = "Extra Text";data = js.extra;Basically, in the last three lines, I set the text of the elements dd_1

and dd_2

(both dd elements, by the way) to the property extra of js, which is assigned a reference to a paragraph element node). Element nodes do not normally have the property extra, so for dd_1

, (which is set to display that property's value before the property itself is set) it's non-existent, as shown by the word undefined

. However, once set, that particular element node has the property extra, and so dd_2

has something to display:

Direct Creation Shorthand

Like arrays, there is a shorthand method of creating objects. Instead of using []

, however, you use {}

. Also, the syntax is slightly different, because you're not dealing with just values but the properties as well. So below is our object, as we created it earlier:

var object = new Object();String = "Something Else";Num1 = 4;Num2 = 5;Num3 = 6;To use the shorthand method, you have to have a comma-separated list of properties and values. The property comes first, then a colon, then the value:

Well, where have we seen that syntax before? Oh, yes: CSS! This works on much the same principle.

In any case, the above code rewritten in shorthand would be:

var object = {String:"Something Else",Num1:4,Num2:5,Num3:6Watch out that you don't use semicolons in there, or things will get messy. Just like in arrays.

Creating An Object Through A Template

A template is a means to create multiple objects that are identical in properties, but not necessarily in values. These separate objects are known as instances, to create them is to instantiate the object. (In direct creation, the object is instantiated when you use var object = new Object()

The template itself is a function. These functions, however, do not return a value in the same way. Below, I've created a template with four variables (Num1, Num2, Num3 and String) called Template.

I know, how very imaginative.

A really important keyword in templates is this, and refers to this instance of the object.

I'll show you what I mean. Below is a template of an object:

function Template(N1, N2, N3, String){this.String = String;this.Num1 = N1;this.Num2 = N2;this.Num3 = N3;Note that the properties of this differ from the names of the variables. That is fine; but when you refer to the properties of an object created by Template, you would use Num1, Num2, and Num3 instead of N1, N2, and N3, since the previous group are specifically stated to be the actual property names.

We create a new instance of this object by calling the template and assigning its value to object below, and declaring it to be a new instance of the object Template. This is exactly like creating a new object (see above) or new array (as shown in previous chapters).

var object = new Template(4, 5, 6, "Something else");When used in such a manner, this means this instance of Num1 is equal to 4, this instance of Num2 is equal to 5, this instance of Num3 is equal to 5, and this instance of String is equal to Something else

.

The advantage to using a template is that we can create as many instances of Template as we need. For example, I created a webpage that used a template to create a new object for every row of a table. Since that table was used to create a seven-month schedule, that template was instantiated more than two hundred times.

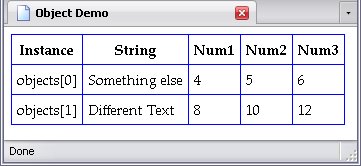

Below, I create an array containing two separate instances of it (though we could use two separate variables entirely).

var objects = new Array(new Template(4, 5, 6, "Something else"),new Template(8, 10, 12, "Different Text")Before I demonstrate more, I should tell you about a trick that's possible: when one refers to the property of an object, you usually have the object, a period, then the property. An example would be to refer to the length of the array objects:

lengthBut it is permissible to act as if the object were an array, and use the property name as a string in place of an index number. The code also refers to the property length:

"length"]This is important, because strings can be manipulated, as you will see in the code that assigns text to elements:

function Text(r, c){return r.getElementsByTagName("td")[c].firstChild;}var trs = document.getElementsByTagName("tr");for(var l = 1; l < trs.length; l++){Text(trs[l], 1).data = objects[l - 1].Stringfor(var l2 = 1; l2 <= 3; l2++){Text(trs[l], (l2 + 1)).data = objects[l - 1]["Num" + l2]As you know, three properties share the letters Num

. Concatenating the strings with the properties' respective numbers allows me to assign their text to text nodes via a loop. Below, each row represents a different instance of the object Template, and you can see their different values:

Adding Methods

A method is a function associated with an object. Making a function a method is actually quite easy: treat the function name like a variable. First, we create the function Get_El, saying that its purpose is to get an element. It can get an element by ID or by tag name, and if the second value is undefined, then treat the first like an ID:

function Get_El(name, num){var el;if(num == undefined){document.getElementById(name);else {document.getElementsByTagName(name)[num];return el;Just a note here: I didn't try to use num as a boolean in and of itself (Example: if(!num)not

right along with falseundefined, but in the case of node lists, 0

refers to the first element in that list. Therefore, only an undefined value will cause it to treat the first value as an ID instead of an element name.

The next two samples deal with direct creation; the third deals with a template:

var object = new Object();Num1 = 4;Num2 = 5;Num3 = 6;String = "Something Else"Get_El = Get_El;var object = {Num1:4,Num2:5,Num3:6,String:"Something Else"Get_El:Get_Elfunction Template(N1, N2, N3, String){this.Num1 = N1;this.Num2 = N2;this.Num3 = N3;this.String = String;this.Get_El = Get_El;var object = new Template();Note that, in the template (which I left otherwise unaltered), I did not add a function variable to the function Template to deal with the new property

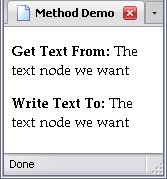

Get_El. Since Get_El is a method, not a property, I don't need to; I pass values to it when I use Get_El through the object. In the following example, I show accessing Get_El through an object created via template, but I also display one minor redundancy:

headfunction Get_El(name, num){var el;if(num == undefined){document.getElementById(name);else {document.getElementsByTagName(name)[num];return el;function Template(N1, N2, N3, String){this.Num1 = N1;this.Num2 = N2;this.Num3 = N3;this.String = String;this.Get_El = Get_El;var object = new Template();bodyvar object = new Template();var fee_fie = object.Get_El("write_to");var foe_fum = Get_El("get_from");firstChild.data = foe_fum.firstChild.data;The variable foe_fum accesses Get_El directly, rather than through object. Since Get_El is a global function, this works:

If you want Get_El to be exclusive to Template so you don't have functions tripping over each other, nesting functions comes in handy.

function Template(N1, N2, N3, String){this.Num1 = N1;this.Num2 = N2;this.Num3 = N3;this.String = String;this.Get_El = Get_El;function Get_El(name, num){var el;if(num == undefined){document.getElementById(name);else {document.getElementsByTagName(name)[num];return el;var object = new Template();A trick that can save some code is assigning the function itself to the property, rather than just the function's name:

function Template(N1, N2, N3, String){this.Num1 = N1;this.Num2 = N2;this.Num3 = N3;this.String = String;this.Get_El = function (name, num){var el;if(num == undefined){document.getElementById(name);else {document.getElementsByTagName(name)[num];return el;var object = new Template();Now, if I try to access Get_El directly, I get an error saying it's undefined. It does not exist outside of the template or objects created thereby. As I said earlier, it's a good way to keep functions from tripping over each other.