The Document Object Model

I really hate to start out with the hairy hocus-pocus, but if I'm going to demonstrate JavaScript properly I don't have much of a choice. So bear with me. Scripting works with and manipulates something known as the Document Object Model (DOM for short), which is basically a model of what elements have what children, attributes, and so on. Knowing how this works is essential to understanding scripting.

A note here: From now on, when I talk about an HTML DOM or document, I will be talking about the DOM of a document with the .html

or .htm

extension, regardless of the actual markup language used. When I talk about XHTML, I will be talking a a document with an .xhtml

, .xht

, or .xml

extension, since that means the document is being read as XML. If I simply say DOM

, then what I'm talking about refers to either.

DOM Nodes

A DOM is made up of nodes. The DOM tutorial on the W3Schools website explains nodes well:

According to the DOM, everything in an HTML document is a node.

The DOM says:

- The entire document is a document node

- Every HTML element is an element node

- The text in the HTML elements are text nodes

- Every HTML attribute is an attribute node

- Comments are comment nodes

(http://www.w3schools.com/htmldom/dom_nodes.asp)

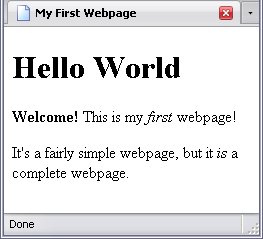

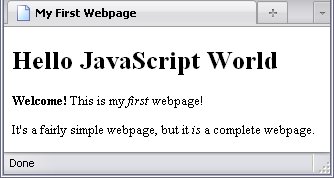

To demonstrate a DOM, I'm going to show you a simple HTML document. You might remember this webpage from Your First Webpage.

Building on what we learned in the portion on (X)HTML, I gave all the descendants of the body element id attributes like I did in Introduction to CSS along with a title attribute for the h1 element. I also added a script element, which we'll use to explore the DOM.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="Content-Style-Type" content="text/css">

<meta http-equiv="Content-Script-Type" content="text/javascript">

<title>My First Webpage</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1 id="h1_1" title="The traditional starting point.">Hello World</h1>

<p id="p_1"><strong id="strong_1">Welcome!</strong> This is my <em id="em_1">first</em> webpage!</p>

<p id="p_2">It's a fairly simple webpage, but it <em id="em_2">is</em> a complete webpage.</p>

<script type="text/javascript">

</script>

</body>

</html>

So let's pick this page apart. The first picture is a diagram of what is nested in what. Remember that the meta element is an empty element, and all its content

is contained in its start tag. Next is what is known as a node tree. It shows what a webpage's DOM looks like, and you can use it like a map. The third is a key telling you what node is what type (I lump document and document type together here).

Document is, of course, the root node (this is very important). The Document Type node corresponds to the Doctype, which is rarely referenced in JavaScript, but the rest of the nodes—or at least nodes of those types—are quite often accessed by JavaScript.

I left out text nodes that contain whitespace and nothing else. I did this for a few reasons:

- I have never heard of JavaScript being used to manipulate those particular nodes,

- the diagram would look a lot more cluttered if I did include them,

- the HTML DOM can be a bit strange when it comes to those nodes.

Specifically, the HTML DOM does not include a text node between the html and head start tag, and according to Internet Explorer, a text node that includes only whitespace doesn't exist. The DOM of an XML document does not have this peculiarity: if there's anything other than coding between two tags, there's a text node there.

I did not omit a text node between the start tag of the first p element and the strong element: if you look at the code, you'll see the start tags for these elements are adjacent, with no intervening text, not even whitespace. Therefore, there is no text node there.

Some of the text for the second paragraph was cut off because it wouldn't fit in the rectangles. But looking at this, you should be able to figure out which nodes are which.

Node Types

There are 12 distinct types of nodes, 4 of which are commonly used in JavaScript.

Each type of node has a specific numerical value which can be used to determine which type of node it is (handy when your script may have to deal with several types).

The Document Node

NodeType numerical value: 9

The document node is the root node. Therefore, every time you want to access a node, you have to start with the document node.

Element Nodes

NodeType numerical value: 1

As I said back in Chapter 2, elements are the building blocks of any webpage, so they are one of the most important types of nodes in any DOM.

Attribute Nodes

NodeType numerical value: 2

Attribute nodes are always child nodes of element nodes.Wherever there is an attribute, there is an attribute node.

Text Nodes

NodeType numerical value: 3

If you have whitespace (which includes spaces, tabs, or new lines), letters, or numbers between two tags of any kind, that's a text node. Seriously. The only type of markup document that wouldn't have a text node at all would be one that read:

That's assuming, of course, that root is the root element. If the two tags on different lines (as shown below), then it would have a text node containing whitespace.

Usually, JavaScript is used to manipulate the text nodes of block or inline elements.

Text Nodes And Child Elements

If you have a paragraph with some text, then an em element (with its own text), then some more text, that paragraph will have text nodes: one before the em element and one after. The text inside the em element element is not considered part of either of the paragraph's text nodes.

From The Code Of The Example Above.

<p id="p_2">It's a fairly simple webpage, but it <em id="em_2">is</em> a complete webpage.</p>

The first paragraph has only two child text nodes as well—remember that the start tag of the strong element directly follows the start tag of the first p element:

<p id="p_1"><strong id="strong_1">Welcome!</strong> This is my <em id="em_1">first</em> webpage!</p>

Character Data Section Node

NodeType numerical value: 4

It is entirely possible that you may want to use the script to refer to an internal stylesheet, script, or content you don't want confused with markup. Of course, this is only used in XML (in this case, XHTML) documents.

Document Type Node

NodeType numerical value: 10

Just in case you were curious. :-)

Accessing Nodes

You can't do anything with an element, attribute, or text node unless you can get at it. Each node has its own special way of being accessed.

By the way, habit alert: I usually end lines of JavaScript code with a semicolon (;

). You may use these or leave them off as you please (for the most part). I use them because I regularly code with PHP, which requires them.

Accessing The Document Node

All nodes in the DOM of any markup document (not just (X)HTML) are accessed through the document node, using the keyword document.

Accessing Element Nodes

Accessing element nodes sometimes requires a method, which I quickly defined back in Dynamic Behavior And Scripting as a procedure associated with an object (in this case, a DOM node). There are two methods that access element nodes:

getElementByIdgetElementsByTagName

By ID

Remember when I said the id attribute was really, really important? This is another reason why. The method getElementById accesses a single element with that specific, unique id value.

This method must be preceded by the keyword document and a period. It might sound confusing but I assure you it's true. Suffice to say for now, if I wanted the element with the ID of p_1

(which is the first paragraph in the sample page), I would do it like this:

document.getElementById("p_1");

See those quotation marks? Those are important. They tell that browser that p_1

is the literal string of text that it's looking for. Oh, and yes, you can use single quotes as well:

document.getElementById('p_1');

By Tag Name

The other method is to get a list of nodes by their tag name. That list

part is important, and I'll explain how to work with it soon. But for now, say you wanted to get a list of all em elements in the webpage. The way to do it is like this:

document.getElementsByTagName("em");

Those quotation marks have the same importance as with getElementById. You may also use this method with getElementById, if you wanted to get a list of elements nested within another specific element. For example, for a list of all em elements nested within the second paragraph, you would do this:

document.getElementById("p_2").getElementsByTagName("em");

And that would give you a list of every single em element nested within the element with the ID p_2

—in this case, emphasis on single

.

Picking From The List

There is a way to choose an element from an element list. This entails following the getElementsByTagName with a number contained in square brackets. But you must remember: most programming languages (JavaScript included) start counting at zero. Which means if you wanted the first em element in a webpage, you would have to say you wanted #0

; #1

would be the second.

document.getElementsByTagName("em")[0];

Now, can you use that method to get, say, the first em element in the second p element?

document.getElementsByTagName("p")[1].getElementsByTagName("em")[0];

Yes. Yes you can.

What Won't Work

document.getElementsByTagName("p").getElementsByTagName("em");

You can only get a list of nodes from a specific element node or the document node, not from a list of nodes.

document.getElementsByTagName("p")[1].getElementById("em_2");

document.getElementById("p_2").getElementById("em_2");

You can only use getElementById with the document node. Besides, since IDs are unique, it's redundant to do it this way, and doing it this way is redundant.

Accessing Attribute Nodes

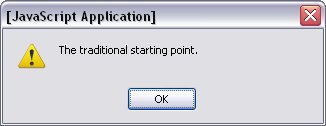

Accessing an attribute uses the method getAttribute. Because attribute nodes are always children of element nodes, to access an attribute node, you have to specify which element node is the parent. Because of this, my demonstration will use getElementById, which gets a single element.

In the example below, I am getting the title attribute of the element with the ID h1_1

.

<h1 id="h1_1" title="The traditional starting point.">Hello World</h1>

document.getElementById("h1_1").getAttribute("title");

Yes, quotation marks are needed again.

What this says is:

- Access the document node.

- From the document node, access the descendant element node with the ID

h1_1

.

- From that element node, access the attribute node with the node name

title

.

Using the alert function I mentioned in Dynamic Behavior And Scripting, we can cause the contents of the h1 element's title attribute to show up in a popup box.

The steps are:

- Access the document node.

- From the document node, access the descendant element node with the ID

h1_1

.

- From that element node, access the attribute node with the node name

title

.

- Show the results of all that in a popup box via the

alert function.

This can actually be used as a working script:

<script type="text/javascript">

alert(document.getElementById("h1_1").getAttribute("title"));

</script>

The result is:

And now that you know what else can go between (

and )

, you should realize why quotation marks are important. Not everything is plain text.

Internet Explorer and Element Class

Internet Explorer treats the class attribute a little differently than most other browsers. Most browsers treat the class attribute like any other attribute. Internet Explorer uses the property className. This is one of the differences between JavaScript and JScript that I mentioned earlier.

Accessing Text Nodes

Manipulating the text in an element is one of the primary uses of scripting, but getting at the text is a little complex. Here are the steps:

- Access the document node, using the keyword

document

- Access the desired element node. I will use the method

getElementByIdh1_1

.

- Access the desired

text node. The keyword firstChild is often used, but it works only if the desired text node is indeed the first child node of the specified element node. For sake of simplicity, that will be the case here.

- Access that text node's text with the keyword

data

The resulting code would be:

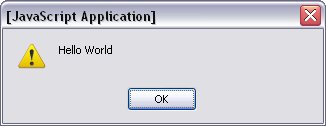

Again, this can be used in a similar fashion with the alert function to create a working script.

<script type="text/javascript">

alert(document.getElementById("h1_1").firstChild.data);

</script>

The result is:

Navigating The Nodes

You can navigate the DOM using the following with element and text nodes (but not attribute nodes).

- parentNode*

- This gets the parent of a specified node.

- previousSibling

- nextSibling

- These keywords refer to an adjacent node with the same parent as the specified node.

- childNodes

- This refers to a list of child nodes of the specified node.

- firstChild

- lastChild

- These keywords refer to the first and last child nodes of the specified node.

The node marked with an asterisk is the only one of these that can be used to refer to the document node, since it is not a child or sibling node.

It is important to remember that these may be used in combination with each other and themselves. For example, take the following line from the code of the first webpage:

<p id="p_1"><strong id="strong_1">Welcome!</strong> This is my <em id="em_1">first</em> webpage!</p>

Getting the text of the strong and em elements is rather simple:

document.getElementById("strong_1").firstChild.data;

document.getElementById("em_1").firstChild.data;

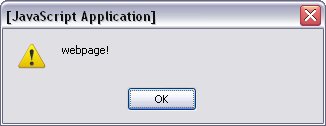

Getting the text outside of those elements is a bit more complex and requires some navigation of the DOM. The simplest to start off with is the word webpage!

: Simply choose the last child node of the paragraph element. To illustrate that this works, I'll have it pop up in an alert box.

alert(document.getElementById("p_1").lastChild.data);

Below is the result

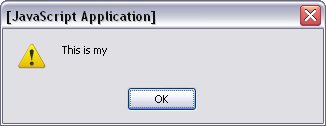

Getting the words This is my

will take a few more, so I'll walk you through them.

- Get the

p element

document.getElementById("p_1")- Get its first child node.

-

document.getElementById("p_1").firstChild

Note that this is the strong element!

- Get the next sibling of the

strong element

document.getElementById("p_1").firstChild.nextSibling- Get the data from that node

document.getElementById("p_1").firstChild.nextSibling.data

Throw that set of instructions into an alert, and This is my

shows up in an alert box:

In this case, the following would get the exact same node:

alert(document.getElementById("strong_1").nextSibling.data);

The reason why I used the p element was to better show navigation.

Manipulating Text Nodes

Extracting the text in a text node is not the only thing JavaScript is used for. Putting text there is even more common. There are a number of properties and methods that allow you to manipulate the DOM, but I am not going to go into great deal about these before explaining more JavaScript to you (this hocus pocus is hairy enough!). I will, however, show you how to manipulate a text node. Let's play around with the h1 element, and change its text to Hello JavaScript World

. Remember the keyword data? That's what we'll be working with.

document.getElementById("h1_1").firstChild.data = "Hello JavaScript World"

This actually sets the text to what we want. The result is below.

I'm saying this now because this is how most of my examples in the following chapters will work.

Cautionary Notes

I'm going to make a few cautionary notes, because JavaScript has more than a few surprises up its sleeve, some of which have thrown me for a loop. First, and most importantly, always remember that a node must actually before you do anything with it.

Script Placement

The above warning is why the placement of a script element is important. If your script uses p elements, but is placed in the head element, you'll get an error, because the script element (which is in the head) will load before the p elements (which are in the body) do—which means your browser will try to access elements that don't exist yet!

For this reason, website developers usually place their script element(s) at the end of the body element. There are ways around this; I'll get to those.

On Text Nodes

A common error with text nodes is to have no text node where you want one. For example, look at the following code:

<p><strong>JavaScript Result:</strong> <span id="JS"></span></p>

This gives document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.dataJS

does not have a text node. For most browsers, a single space is sufficient to fix this problem. HOWEVER...

According to Internet Explorer, a text node containing nothing but white space does not exist.

No matter how many tab characters, spaces, and new lines you have in a text node, if it's whitespace only, Internet Explorer will not acknowledge it as an existing node. If you are wondering Will that make a difference with firstChild, lastChild, childNodes, and nextSibling

, the answer is yes, and thank you oh so much for dredging up such pleasant memories.

If you want a space as a placeholder, you have to use something known as a non-breaking space, which has the entity reference

and the entity code of

(

if you're using UNICODE codes).

<p><strong>JavaScript Result:</strong> <span id="JS"> </span></p>

The tbody Element And HTML DOM

Subtitle: And How They'll Make You Tear Your Hair Out

The HTML DOM has one major peculiarity when it comes to tables: it always assumes the tbody element is a child of each table element whether the tbody tags are there or not. Because of this, if you intend to use a client-side scripting language (JavaScript isn't the only language with this issue; I think VBScript has it as well) to manipulate the rows of a table, you must take into account that if tr elements are seemingly child elements of a table element, they are actually the children of a tbody element, never a table element. Otherwise, you may be in for a world of frustration.

Try giving some styling using the selector tbody td when the page has no tbody elements; you'll see what I mean.

With an XHTML DOM, this is not a problem.

When you look at the series of commands that allow you to access a text node, it becomes clear that typing document.getElementById("JS").firstChild.data

over and over again will quickly become tedius. So how to make it easier? Use variables, of course. That's in the next chapter.