The Core Attributes

There are four attributes known as the core attributes which are used by almost every element in HTML. Their functions vary so widely that they have little in common save their ubiquity. These attributes are:

- title

- class

- style

- id

The title Attribute

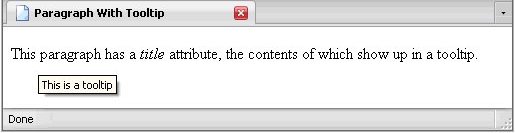

The title attribute contains descriptive text about the element. You often see it in a tooltip (illustrated below in the Usage section).

Usage

The title attribute is a text-type attribute—that is, it contains plain text. The text does not need to be unique, nor does it have to have anything to do with the element it's supposed to describe, though it is good practice to avoid such non sequitors.

Below is an example of how the title attribute works:

And the result is below:

The title attribute is a perfect example of why you should not omit the quotation marks.

Here, I have omitted the quotation marks and now the browser is confused. Where does the attribute begin and end? Is the browser supposed to read one (title=This is a tooltip) or four attributes (title=This, is, a, tooltip)? And what if your intended text had an equal sign in it, which is perfectly legitimate? Omitting quotations in an attribute will only confuse your browser, and I warned you about confusing your browser. By the way, most browsers will read the above title attribute as only containing the word "This".

As one last note, it is also a perfect example of why one needs to be sure to place the element name first: the title attribute shares its name with the title element.

The class Attribute

The class attribute is used to group elements together. You can use the same class for several elements, and even have an element having two classes (which means it belongs to two different groups). An analogy would be a university: each student may be in many classes, and each class may have many students.

At the risk of getting a little ahead of myself, class does not have much effect on raw (X)HTML like you're working with now aside from giving yourself a way of knowing what element is used for what, but when it comes to formatting—that is, deciding on how your webpage will look, which is handled by Cascading Style Sheets—the class attribute is indispensable.

I'll talk about formatting a webpage and Cascading Style Sheets later.

Usage

Like the title attribute, you can enter whatever text you please without breaking the rules set down by the (X)HTML DTDs. Unlike the title attribute, the class attribute requires a fairly specific format to be of any use.

Rules of Class Names.

- Class names may only contain hyphens, underscores, letters, and numbers.

- Class names may not start with a number.

- If an element belongs to multiple classes, the class names are separated by spaces.

Again, if you flout these rules, an (X)HTML validator won't pick up on it, but you need to follow these rules if class is to be of any use.

In the above example, the first paragraph of the class Core-Class-1

, and the second is of Core-Class-2

. The 3rd paragraph does not have a class, but the strong element belongs to both classes of elements.

Remember this example from earlier?

This is the proper way to do it:

The style Attribute

The style attribute is used to change the actual appearance of an element: what font it is in, what colour the text is, the colour of the background, whether or not it is bold, underlining, the size of the text, and so on.

Usage

Like the title and class attributes, style can contain whatever text you like. Like the class attribute, for the style attribute to be of any use, its contents must adhere to a specific (and, amongst attributes, unique) format.

To avoid confusing you, I'll start with two properties that have the same set of values: color and background-color. (The former refers to text colour, the latter is self-explanatory). They have many possible values, but these 16 colours should do just fine for now (colours separated by a slash are exactly the same):

- Aqua/Cyan

- Black

- Blue

- Fuchsia/Magenta

- Gray/Grey

- Green

- Lime

- Maroon

- Navy

- Olive

- Purple

- Red

- Silver

- Teal

- White

- Yellow

The format of the style attribute is really quite simple: it contains a list of one or more declarations, each of which consists of a property (like color) and a value (like red).

style Attribute- property

- The aspect of the element you want to control (for example, text colour or background).

- :

- Separates the property and the value.

- value

- What you want that property to be (for example, what colour you want the text or background).

- ;

- Ends the declaration, which allows you to add more declarations as necessary.

For example, if you want to set the text colour of a paragraph to blue, all you have to enter is:

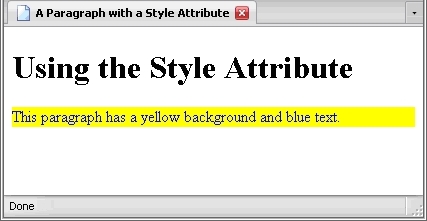

If you want to set the background colour of a paragraph to yellow, the attribute would be:

If you want both, they can be used together like this:

The order the declarations are in does not matter as the effect is the same. The effect of either arrangement can be seen below:

Below is a list of some other properties that you can use with the style attribute:

- text-decoration

- This controls whether the text is underlined, struck through, has a line over it, is blinking, or any combination thereof. The keywords are:

- underline

- overline

- line-through

- blink

- none

- font-weight

- This controls how heavy the font is, but for the most part, that's limited to whether or not it's in bold. The most commonly used keywords are:

- bold

- normal

- font-size

- This can set the size of a font, whether in points, which is 1/72 of an inch, percentage of the text around it, centimeters, or some other value.

- font-style

- This sets whether a font is in italics or not. Its keywords are:

- italic

- oblique

- normal

italicandobliquehave exactly the same effect. - font-variant

- This allows you to have lower-case letters show as small capital letters. Its keywords are:

- small-caps

- normal

I'll explain the rest of the properties when I explain CSS; this is just a taste of what you can do.

The id Attribute

The id attribute—short for identity

—is perhaps the most important attribute of all. This type of attribute is used to specify a single element on any given page.

Perhaps you have seen web addresses with a hash mark (#

) and a word after it. That is the most visible use of an ID attribute.

Usage

The id attribute differs sharply from the title, class and style attributes. In the latter three, you may technically enter whatever text you like without causing an error on an (X)HTML validator. Conversely, if you flout the rules of the id attribute, you will get an error.

Rules of ID Names

The rules governing id attributes are like that of the class attribute, but slightly more stringent. The values of each id attribute must:

- contain only letters, numbers, hyphens, underscores, periods, and colons.

- start with a letter

- must not contain spaces

- be unique within that document

The last rule is of particular import: each id attribute exists to identify one and only one element, regardless of the element name.

Valid ID Values

- id="tooltip"

- id="tooltip1"

- id="tooltip.2"

- id="meaning_of_life"

- id="meaning_of_life:definition"

- id="Top"

- id="Bottom"

- id="Header-1"

Invalid ID Values And The Reasons

- id="1tooltip"

- The above starts with a number.

- id="tooltip 2"

- The above has a space before the "2".

- id="_meaning_of_life"

- The above starts with an underscore.

- id="meaning_of_life@definition"

- The above uses the "@" character.

- id="Top Left"

- The above one has a space, as this was an attempt to give an element TWO IDs, which is not allowed.

- id="-Bottom"

- The above starts with a hyphen.

- id=""

- You may not have an

idattribute with no value. If that's what you have, omit the attribute altogether.

ID Examples

The two paragraphs have exactly matching ID attributes, which will confuse your browser and cause problems. Remember, no two elements in any single markup document can have the exact same value for an id attribute. If you want something like the above, using similar but slightly different IDs is acceptable:

The addition of the numbers distinguishes the two elements, satisfying the requirement of unique values for id attributes.

A Final Note on class And id

One use for these two attributes has nothing to do with coding, but simply keeping track of your document. They can be given names that tell you what each element is for. For example, a paragraph with the class name of "footnote" and id of "footnote_1" gives you a very good idea of why you included that paragraph.