Server-Side Includes

File Extension: .shtml

The only server-side language I'll demonstrate at all is Server-Side Includes—SSI for short—since it's the simplest server-side scripting language I know of and it illustrates the concept of server-side scripts reasonably well.

SSI takes the contents of various text files and assembles them into a single HTML document. I say HTML

because that's about the only language SSI is used with—and if you use XHTML code with SSI, the page will still be read as HTML unless the server is instructed otherwise.

Because the browser is only sent the fully-assembled page, the page's elements do not have to begin or end in the same text files, they only need to be complete in the finished product.

So what would be put into these text files? Well, back in Procedures, I stated one reason procedures were used was so that code used repeatedly didn't need to be typed every time it was needed.

SSI uses the same concept; in this case the code is (X)HTML and used repeatedly

means used on multiple pages

.

The most common things to be repeated are:

- the document head (or a portion thereof)

- the site navigation

- and the webpage's footer (if there happens to be one).

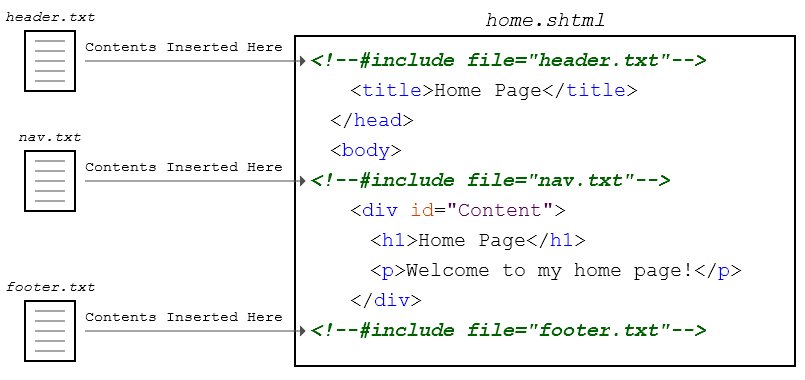

Here's an example, showing a page with most of its head in one text file, its navigation in another file, and a footer

containing some script elements and the end of the document. Note that the extensions of all these are .txt, which means they are plain text files. This is fine; when the page is sent, they will be read as HTML. The only time the extension matters is if a file to be included use SSI itself; then you have to use the .shtml file extension.

html lang="en" dir="ltr">head>meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">meta http-equiv="Content-Style-Type" content="text/css">meta http-equiv="Content-Script-Type" content="text/javascript">base href="http://www.mywebsite.com">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/setup.css">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/screen.css" media="screen">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/print.css" media="print">ul id="Navigation">li id="Home_Link"><a href="home.shtml">Home</a></li>li id="About_Link"><a href="about.shtml">About</a></li>li id="Links_Link"><a href="links.shtml">Links</a></li>ul>script src="./hovers.js"></script>script src="./nav_hilites.js"></script>body>html>Important note: The demonstrated code above contains the entire contents of those files; I have left nothing out. If these look like incomplete HTML files, that's because they are.

Notice the use of the base element in head.txt. In Comments, HTML, Head and its Children, Body, I mentioned this element and said it established an absolute URI to calculate relative URIs. This is where it comes in really handy—head.txt could be used in any document using server-side includes, so the link elements would run the risk of pointing to the wrong file or a non-existant one—except the base element establishes exactly what their URIs are relative to.

The command to include a file is fairly simple, and looks a cross between a start tag and a comment.

Below, I show what home.shtml looks like.

home.shtml Filetitle>Home Page</title>head>body>div id="Content">h1>Home Page</h1>p>Welcome to my home page!</p>div>It appears a lot is missing here: the start tag for the head element, the end tag for the body element, both tags for html, the Doctype itself...

Actually, they're there alright; they are simply in the files to be included instead of home.shtml itself. The Doctype and the start tags for html and head are in header.txt, while the end tags for html and body are in footer.txt.

The diagram below shows how the server assembles the page according to the SSI commands, and the code below the diagram is the result.

html lang="en" dir="ltr">head>meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8">meta http-equiv="Content-Style-Type" content="text/css">meta http-equiv="Content-Script-Type" content="text/javascript">base href="http://www.mywebsite.com">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/setup.css">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/screen.css" media="screen">link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="./Formatting/print.css" media="print">title>Home Page</title>head>body>ul id="Navigation">li id="Home_Link"><a href="home.shtml">Home</a></li>li id="About_Link"><a href="about.shtml">About</a></li>li id="Links_Link"><a href="links.shtml">Links</a></li>ul>div id="Content">h1>Home Page</h1>p>Welcome to my home page!</p>div>script src="./hovers.js"></script>script src="./nav_hilites.js"></script>body>html>And voilà: four incomplete HTML documents become a single complete one. In this case, there's no sign to tell where one file ends and the next begins—you have to compare this to the constituent files; since most users won't (and shouldn't) have access to those files, they won't be able to do that comparison.

You will also notice that the include

commands are nowhere to be seen in the final result. If they are, then something's amiss; a server's processing instructions should not appear in the browser.

Since the code for the header, navigation, and footer comes from a single file, you only need to edit that file; the server-side instructions will cause that to affect every page that uses that particular file, much like changing an external stylesheet will affect every page that uses that stylesheet.

It's important to remember that when a text file is included, all its contents end up in the final result. I remember seeing the code of a webpage created by someone who thought every file containing any HTML code required a Doctype; the home page ended up with eight of them scattered throughout the code...

It wasn't pretty.

Dynamic Content

Static content always remains the same, since it is based on the coding of an HTML document or its perephiral files (such as stylesheets or scripts). Even if you interact with a webpage through JavaScript, the code never changes; reload the page and it's all back to normal.

Dynamic content, on the other hand, can change; the very code the browser receives can be altered without the document's code being touched. One example (again used in SSI) is when a page was last modified. This particular instruction is:

File Last ModifiedCommand

When the server encounters this command, it will check the file (in this case, links.shtml) to see when it was last changed. This might look like static content at first glance—particularly if the file hasn't been updated in a while. But when it is updated, the information from the server regarding this command will change. Thus, dynamic content. A very popular use of this command is:

File Last ModifiedCommand

p>Links updated on <!--#flastmod file="links.shtml"-->.</p>If the page was created at around a quarter after three in the morning on August 4, 2009, that paragraph would read something like Links updated on Tuesday, 04-Aug-2009 03:14:16 Mountain Daylight Time

. If it was updated on September 5, 2011 at 11:20 AM, the paragraph would then read Links updated on Monday, 05-Sep-2011 11:20:28 Mountain Daylight Time

.

A note here: Mountain Daylight Time

refers to the time zone I'm in as I use that command to get an SSI timestamp.

A look at the code sent to the browser would show the following:

File Last ModifiedCommand

p>Links updated on Monday, 03-Aug-2009 03:14:16 Mountain Daylight Time.</p>p>Links updated on Monday, 05-Sep-2011 11:20:28 Mountain Daylight Time.</p>But let's say that this bit of coding was in index.shtml. It was links.shtml that was edited, not index.shtml, yet the content of index.shtml has changed. This is because the server sent different information to the browser due to the SSI command pertaining to the last update of links.shtml. That is an example of dynamic content.